Unstable and evanescent. Impalpable and unverifiable, they seek every medium to try to come to life. A life of their own, invading their silence.

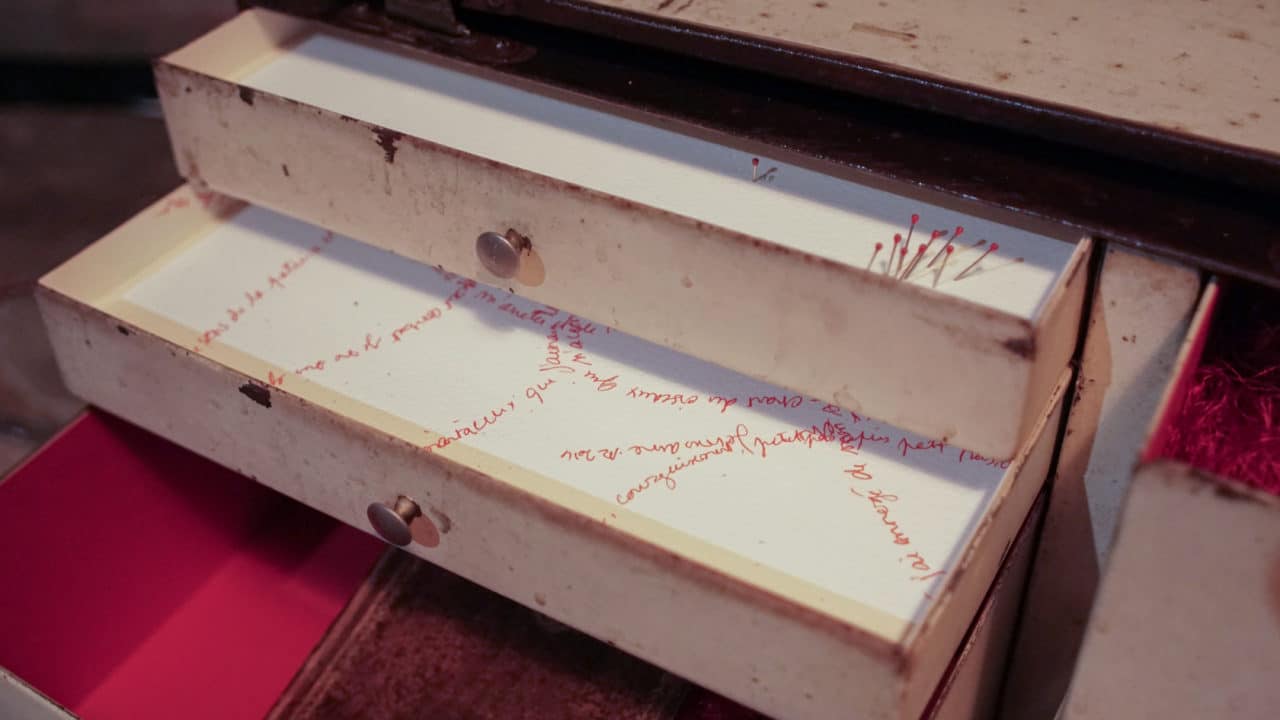

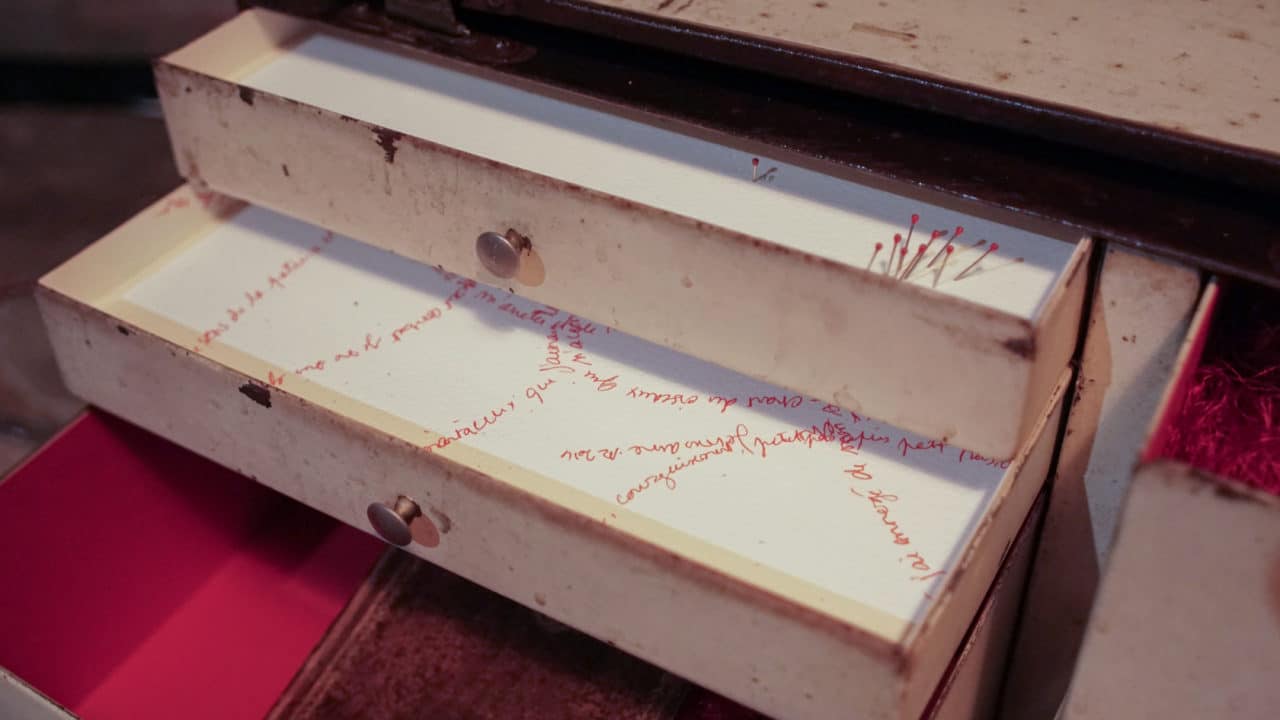

The place of memory was a small piece of furniture containing old glass boxes and endless drawers made of wood bent to hold them together. Here, I had collected books with evocative names: Me- tamorphosis, Divine comedy, the Imprint of God and Mes pri- sons. I’d also put in the Jewish, Christian and Muslim Bibles, as well as a few fragments of moults and other photographic talismans. The whole thing was arranged like a small library that could be accessed from either side and which had been abandoned there over the years.

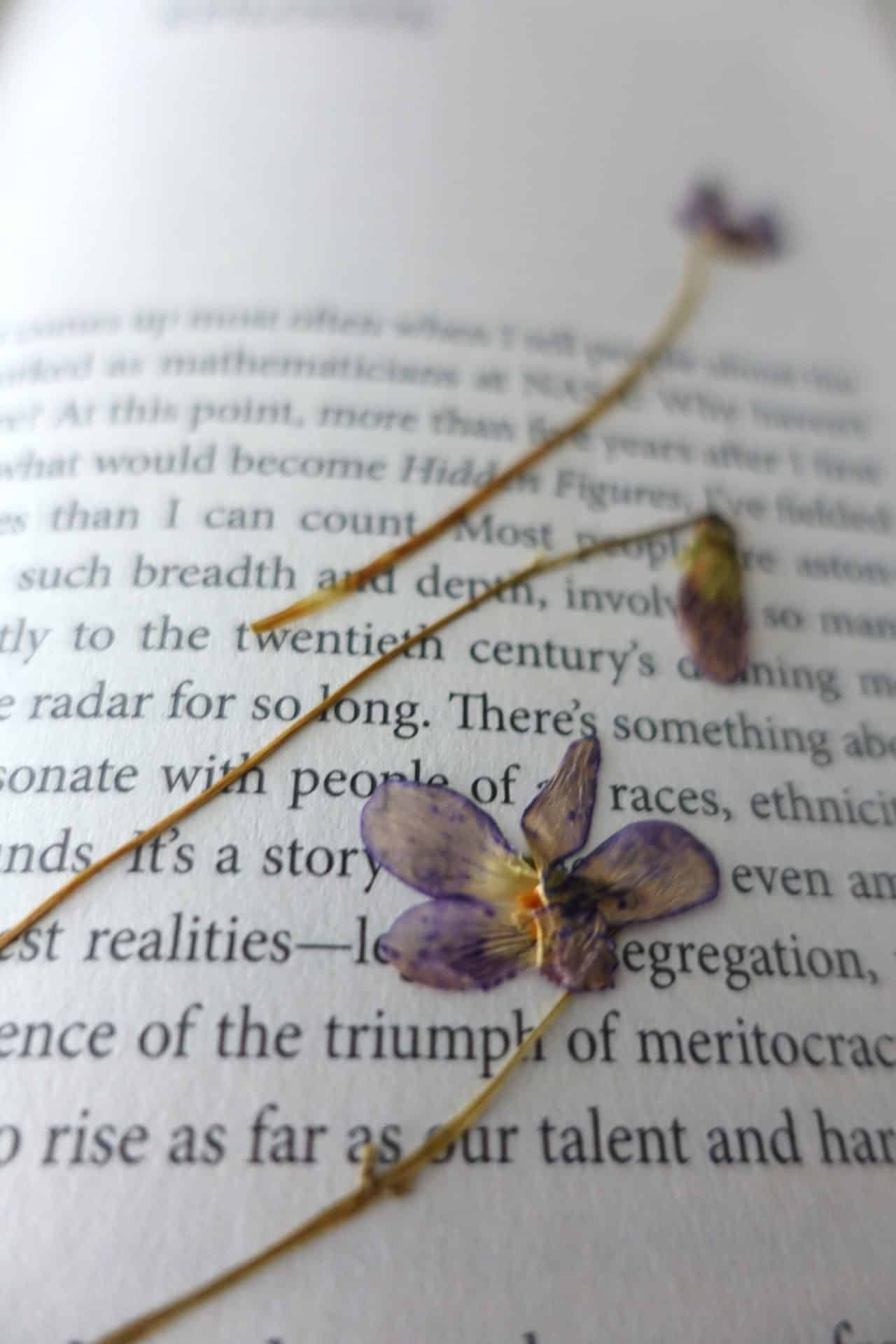

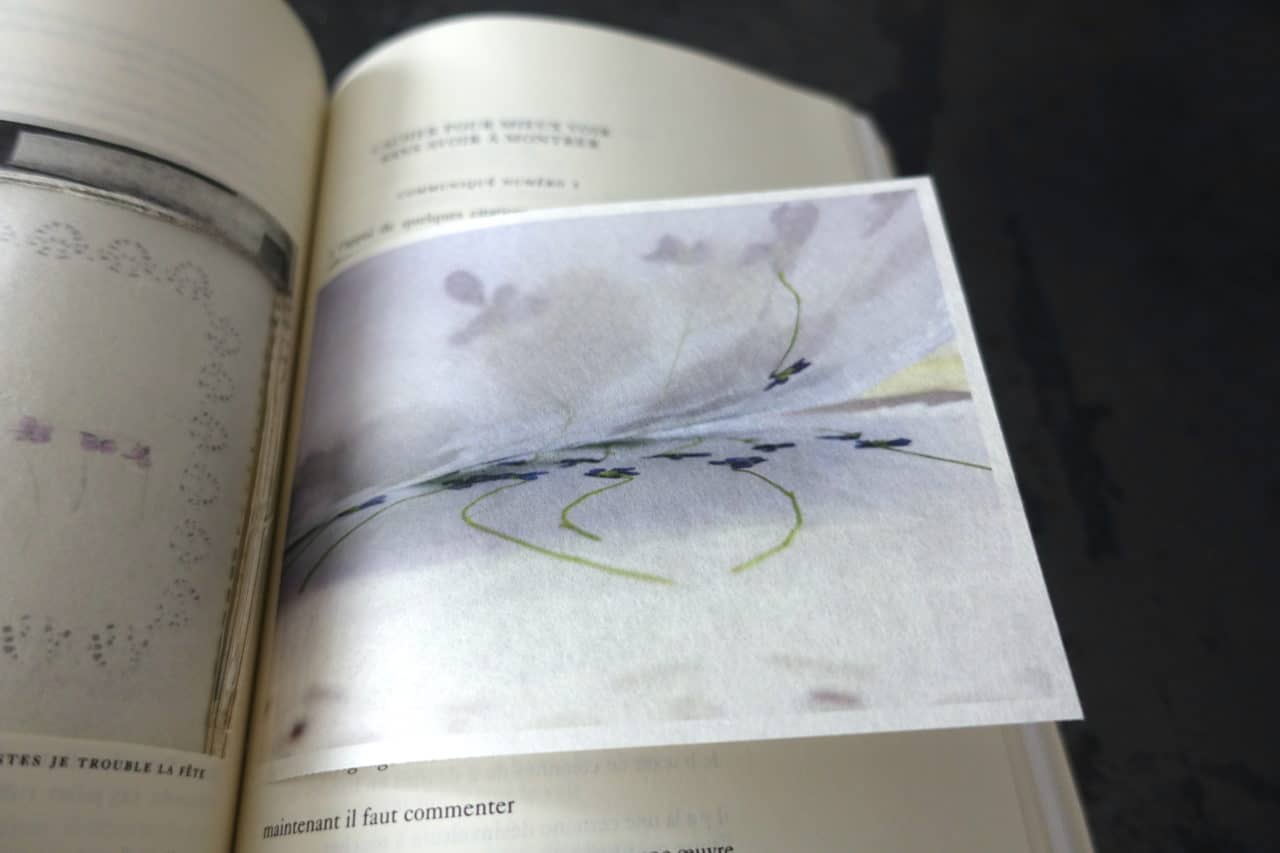

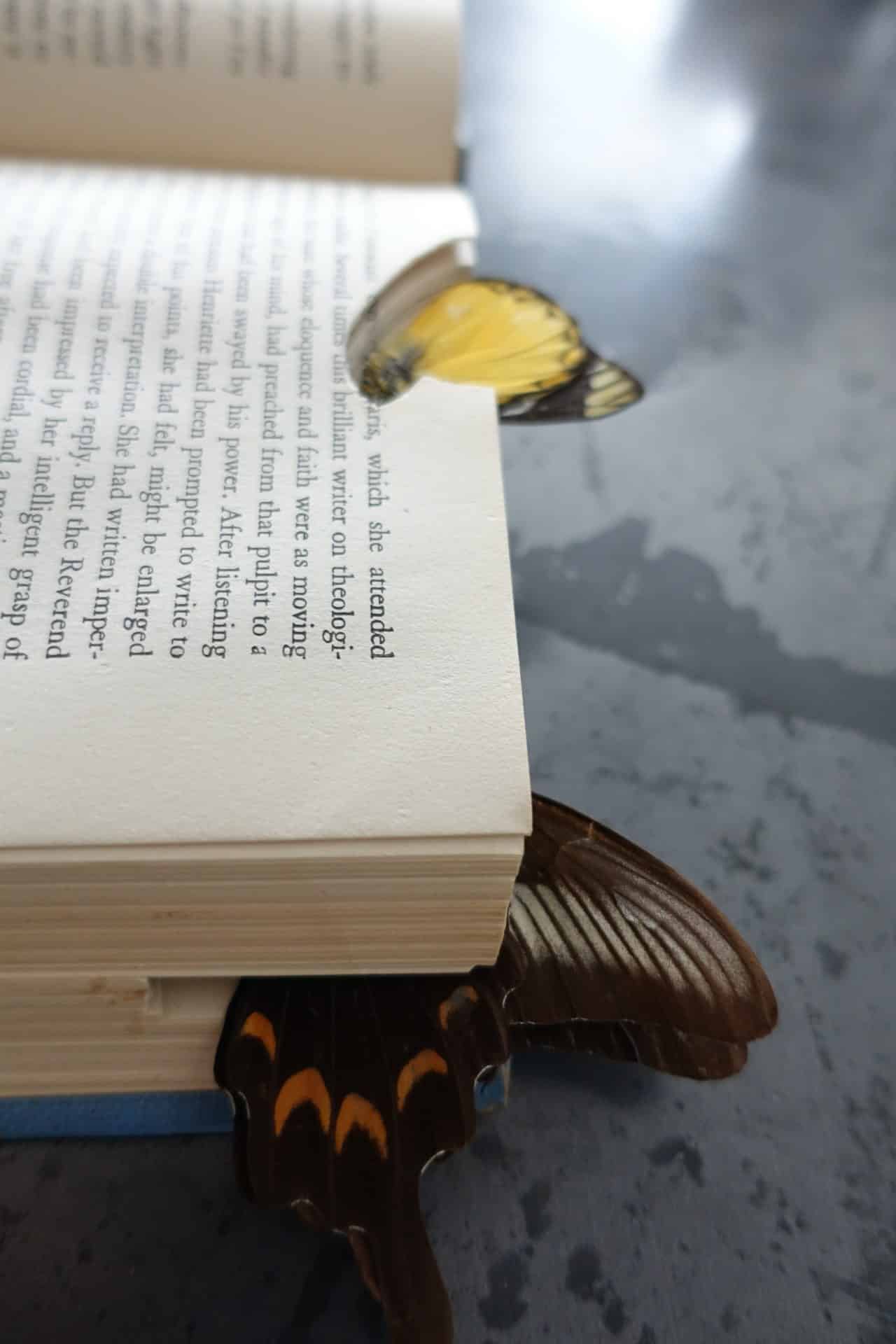

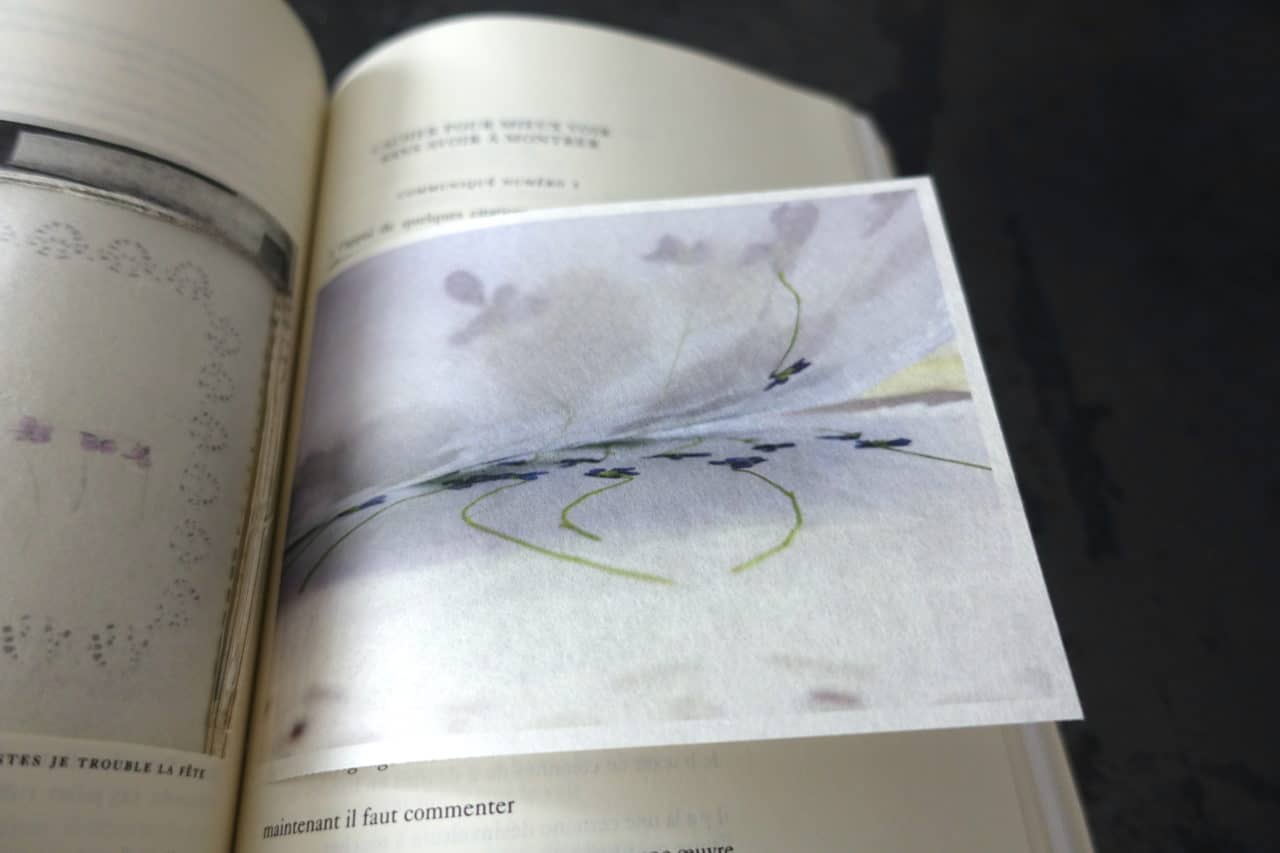

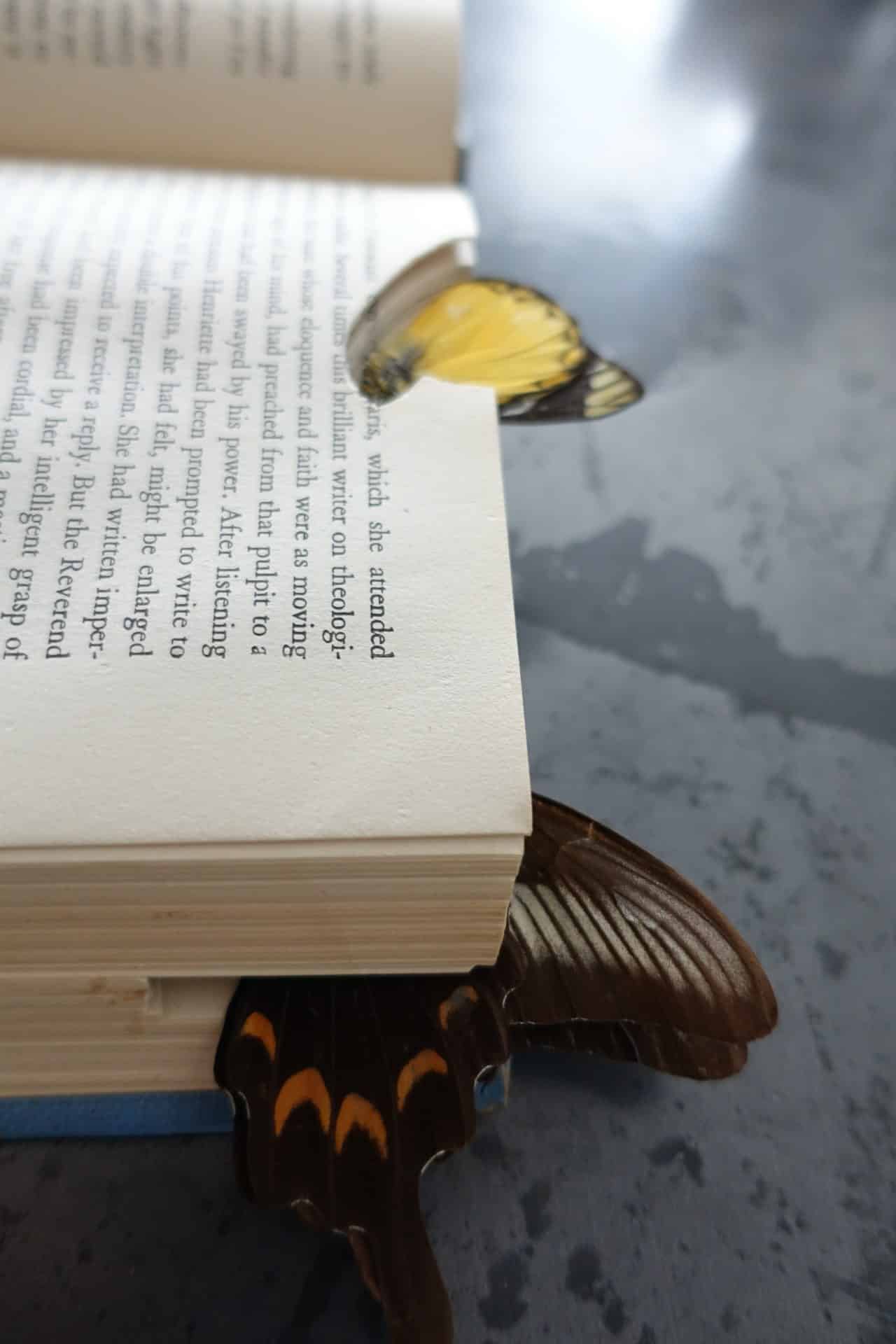

If you were curious enough to approach and open the door, if you were unaware that you were holding a work of art rather than a book, you would discover inside that the words had been hollowed out to make way for another, more visual and just as symbolic world. In the drawer, butterflies had made their cocoon and were ready to fly away or to stay, transforming the chrysalis into a shroud.

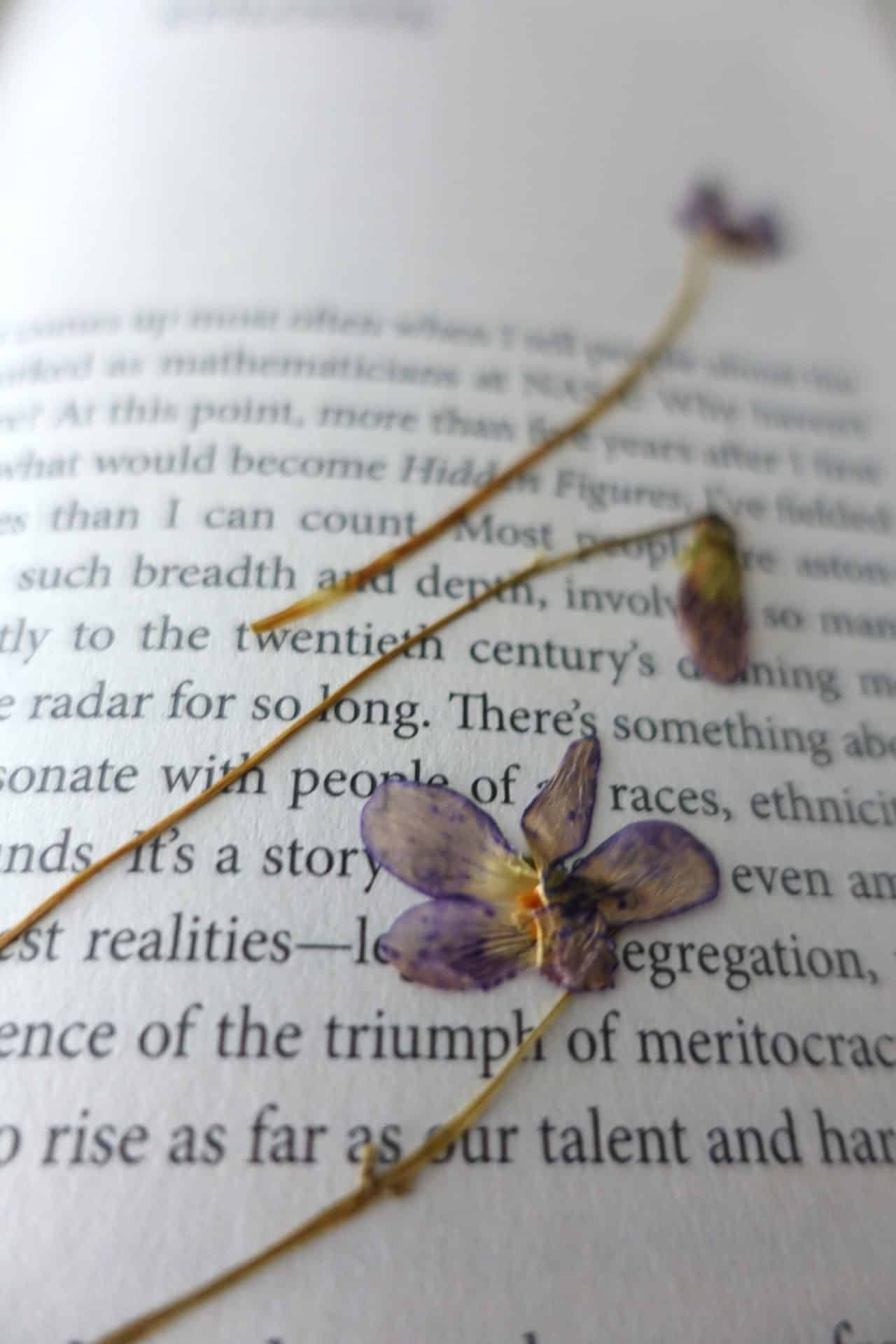

In the Bibles, in Deuteronomy 22 verses 6 and 7, there were souvenir pictures of birds being buried, in boxes a vase of tears or a feathered book, in boxes of fallen bark illuminated after the trees had moulted, and a thousand other details that took the curious into a world from which I hoped they would find the courage to accept their present in order to walk towards the future.

In the winter-cooled but warm space of this brick building, I tried to look to the past for reference points for the paths to come. I thought that by unearthing past mutations I would be able to measure and reduce the distance between fear and action. If I’d been able to face myself in the past, I’d be able to take the plunge again. What I hadn’t envisaged was the magnified view of things that had to do with times that were blessed because they were past.

Unstable and evanescent. Impalpable and unverifiable, they seek every medium to try to come to life. A life of their own, invading their silence.

The place of memory was a small piece of furniture containing old glass boxes and endless drawers made of wood bent to hold them together. Here, I had collected books with evocative names: Me- tamorphosis, Divine comedy, the Imprint of God and Mes pri- sons. I’d also put in the Jewish, Christian and Muslim Bibles, as well as a few fragments of moults and other photographic talismans. The whole thing was arranged like a small library that could be accessed from either side and which had been abandoned there over the years.

If you were curious enough to approach and open the door, if you were unaware that you were holding a work of art rather than a book, you would discover inside that the words had been hollowed out to make way for another, more visual and just as symbolic world. In the drawer, butterflies had made their cocoon and were ready to fly away or to stay, transforming the chrysalis into a shroud.

In the Bibles, in Deuteronomy 22 verses 6 and 7, there were souvenir pictures of birds being buried, in boxes a vase of tears or a feathered book, in boxes of fallen bark illuminated after the trees had moulted, and a thousand other details that took the curious into a world from which I hoped they would find the courage to accept their present in order to walk towards the future.

In the winter-cooled but warm space of this brick building, I tried to look to the past for reference points for the paths to come. I thought that by unearthing past mutations I would be able to measure and reduce the distance between fear and action. If I’d been able to face myself in the past, I’d be able to take the plunge again. What I hadn’t envisaged was the magnified view of things that had to do with times that were blessed because they were past.